Louvre Museum: Top 10 Things to See

The Louvre Museum in Paris is home to some of the world's most treasured artistic masterpieces, and its collections span thousands of years and multiple continents.

Louvre Museum: Top 10 Things to See

The Louvre Museum in Paris is home to some of the world's most treasured artistic masterpieces, and its collections span thousands of years and multiple continents.

Among the Louvre’s countless gems, there are ten works of art and cultural craft that stand out as true icons of the museum. These paintings, steles, and sculptures are the must-see of this magnificent museum.

Some of them are known for their historical significance and role in shaping the culture and art around them, some others for their artistic merit and technical achievements, and others yet for their impeccable preservation throughout millennia.

The Mona Lisa

At the top of the list is the Mona Lisa, arguably the most famous painting in the world. Painted by Leonardo da Vinci in the early 16th century, the enigmatic smile of the woman in the portrait has captivated generations of viewers and remains a symbol of the Louvre itself.

Considering that she hangs behind bulletproof glass and that thousands of spectators flock to the Louvre just to see her, you might be a little disappointed to find out that the painting is actually rather small and modest. What is then the reason behind the fascination that this piece has been eliciting from the public for centuries? Much like the Mona Lisa’s mysterious smile, the reasons for its popularity are also unclear.

Among the various factors that brought it such fame, we can certainly name Leonardo da Vinci’s status as a genius and skilled artist, as well as the painting’s undeniable technical mastery. In fact, the three-quarter pose, the realism, and the use of the sfumato technique, all render a level of visual complexity unique in paintings of the time.

However, much of the interest around the Mona Lisa was aroused after its theft in 1911. For two years, after which the piece was found and returned to the Louvre, the theft brought it worldwide attention and immense media interest, which in turn made millions around the world invested in the missing painting and its story.

Venus de Milo

Next on the list is the Venus de Milo, a stunning Hellenistic statue dating back to the 2nd century BCE, which is believed to depict the goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite. The statue’s graceful lines and exquisite detail make it a masterpiece of ancient Greek sculpture.

The Venus de Milo, in Parian marble, is over 6 feet tall and shows the half-clothed goddess leaning on one leg. The statue has famously no arms, which makes her original posture unclear. It has however been hypothesised that she might have been sculpted hand spinning.

Interestingly, the Venus de Milo’s status as a Greek artistic icon didn’t come about until years after its discovery. You might be surprised to find that the reasons for it are mainly French propaganda efforts.

After France had to return some of their most iconic and precious pieces (among which Laocoon and His Sons and the Venus de’ Medici), the Louvre was in search of pieces to promote as great treasures in order to regain national pride and to boost its own relevance in the artistic scene. This responsibility fell on the Venus de Milo, who has since been praised as the epitome of graceful beauty.

The Liberty Leading the People

Often wrongly thought to be an iconic image of the French Revolution, the Liberty Leading the People, by Eugène Delacroix is actually a painting of the July Revolution of 1830. The piece depicts a bare-breasted woman (Liberty personified) holding a waving French flag as she leads a crowd of revolutionaries forward.

The painting captures the spirit of the age, using allegory to depict the struggle for freedom and democracy. The Phrygian cap worn by Liberty had become a symbol of freedom since the first French Revolution (1789). Each person in the crowd following her represents a different social class (the urban workers, the students, the bourgeoise), all united in the fight for equality.

A mound of corpses and rubble acts as a kind of pedestal for Liberty and her followers, while at the same time being a reminder of the violence of the struggle against power for the audience.

The painting’s legacy is so enduring and its impact on the collective imagination so strong that the piece is believed to have influenced Victor Hugo into writing one of his major novels, Les Misérables. As such, the painting has gained popularity in popular culture as a symbol of emancipation and rebellion against oppressive domination.

The Great Sphinx of Tanis

Among the Louvre’s extensive collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts is the Great Sphinx of Tanis. A sphinx is a mythical creature with the body of a lion and the head of a human. In Ancient Egypt, the sphinx was seen as a protector of temple doors and an incarnation of royal power at once.

The monumental Sphinx of Tanis, which stands 6 feet tall and almost 16 feet long is all the more impressive, as it was carved from a single block of granite. The exact date of the Sphinx’s creation is unclear, but it could be as early as the 26th or 27th century BCE.

Regardless of its origins, the statue is a testament to the skill and artistry of ancient Egyptian sculptors and is one of the most impressive works of art in the museum.

The Four Captives sculptures

The Captifs sculptures are another highlight of the Louvre’s collections. The figures, four prisoners in various states of struggle and despair, symbolise the four nations defeated by France at the time of the Treaty of Nijmegen: Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, Brandenburg, and Holland.

Each nation is paired with a figure of a different age group and attitude to his own captivity. As you are in front of the sculptural group, you will find that the Captives’ turned heads suggest you walk around them in a clockwise direction, going from an old figure to a young one to an old one again, appreciating each statue’s unique composition.

In the corner is Brandenburg, a grief-stricken middle-aged man dressed in Barbarian clothes. His position and expression speak of deep sorrow and suffering. Next to him is Spain, presented as a young man with flowing hair, whose body language and upturned gaze suggest hope.

Next is the Holy Roman Empire, an old, long-bearded man wearing a Roman-style tunic. His downturned position expresses resignation and defeat. Holland is again a young man, this time with a short beard, that seems in the act of thrusting forward in a gesture of rebellion and restlessness.

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, a sculpture by Antonio Canova, depicts the story of the mythological lovers Psyche and Cupid. The sculpture captures the moment when Cupid brings his beloved back from her slumber with a kiss, transforming her from a mortal into a goddess.

One of the distinctive features of the sculpture is the variety of carving techniques used to achieve contrasting materials. While the two lovers’ skin looks smooth and soft to the touch, the drapery looks heavy and the rock underneath rough. The curls of the hair and feathers are also rendered with incredible realism.

The delicate beauty of the piece is a testament to Canova’s skill as a sculptor, which has made it a masterpiece of Neoclassical sculpture. What’s particularly interesting about it is that it is meant to be observed from all angles, as there is no single point of view from which you can appreciate both lovers’ faces.

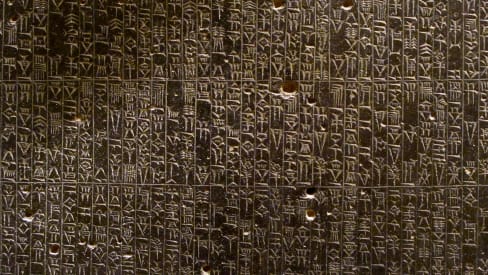

The Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is an ancient Babylonian law code dating back to the 18th century BCE. The code is inscribed on a black basalt stele and in its 4,130 lines it contains a prologue and epilogue in poetic style and almost 300 laws covering everything from economic provisions and property rights to family law and criminal offences.

The stele is the longest and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East, as well as being the best organised. As such, it provides a fascinating glimpse into the ancient world and concrete proof of the influence of centralized government on the personal and professional lives of its people.

The code is believed to have been influenced by earlier Mesopotamian law collections, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, as well as having in turn influenced later law codes, both in the region and outside, including Mosaic Law and Graeco-Roman laws (thus influencing modern understanding of law as well).

The Coronation of Napoleon

The Coronation of Napoleon, a massive painting by Jacques-Louis David, depicts the crowning ceremony of Napoleon Bonaparte at Notre-Dame de Paris in 1804. With the event, Napoleon thus became Emperor of France. What’s impressive about this oil painting is not only its legacy as a masterpiece of Neoclassical art, but it is also its size: it is about 10 metres (33 feet) wide and over 6 metres (20 feet) tall.

Both the gigantic size and the richness in details perfectly capture the pomp and ceremony of the event, as well as the spirit of self-importance typical of Napoleon. Although an original sketch of the piece depicted Napoleon in the act of crowning himself, the finished painting does not show his coronation but rather his wife’s. It is then Emperor Napoleon - and not Pope Pius VII, as would have been customary - dressed in Roman-style robes, to crown his wife Joséphine de Beauharnais as Empress.

Most of the figures present are symbolically placed and dressed, as was customary in paintings of the time. In fact, many of the people depicted (like Maria Letizia Ramolino, Napoleon’s mother, and Joseph Bonaparte, his brother) did not actually attend the ceremony and were added by the artist under the express wishes of the family members or Napoleon himself.

The Sleeping Hermaphroditus

The Sleeping Hermaphroditus is an ancient marble sculpture depicting a life-size sleeping Hermaphroditus. While the figure on the bed is an original antique sculpture unearthed in Rome in the 17th century, the buttoned mattress on which the ancient piece rests was sculpted in 1620 by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Bernini’s addition is extremely realistic, appearing soft to the touch and plush.

The subject of the sculpture is Hermaphroditus, the two-sexed Greek god. The form clearly references Hellenistic portrayals of Aphrodite and a feminised Dionysus, with soft feminine curves and male genitals. According to Greek tradition, he was created when a naiad prayed to the gods to be forever united with the handsome child of Aphrodite and Hermes, whom she had fallen in love with. The gods, answering her prayers, merged the two into one.

Hermaphoditus thus became a symbol of androgyny and effeminacy. In ancient Greece and Rome, the god was actually a very popular sculptural subject. Suffice it to say that several different versions of a sleeping Hermaphroditus - some of which are exactly in the same pose as the one in the Louvre - were discovered throughout the years.

The Wedding at Cana

Finally, the Wedding at Cana, an oil painting by Paolo Veronese, depicts the biblical story of Jesus turning water into wine at a wedding feast. The painting symbolises the coexistence of the joys of life, their transitory nature, and mortality. It features a cast of dozens of figures, each rendered with remarkable skill and detail.

The rather large painting (22 feet by 32 feet) makes brilliant use of Mannerist artistic tools, like distortion of the space, artifice, tension, and heavy cultural and religious symbolism. Still, the piece maintains the harmony in composition typical of Renaissance art.

Of course, the Louvre contains many more important works and thousands of masterpieces. So many, in fact, that it would be impossible to see them all even in an entire day (or two!). Let these ten pieces be a representation of some of the finest works of art that you can find in the museum.

They are a testament to the enduring power of human creativity and imagination and its wonderful diversity. The Louvre Museum is truly a treasure trove of artistic and cultural riches, and these ten works simply stand out as icons of this remarkable institution.

If you want to know all about the museum, its art, and its various departments, have a look at our dedicated article.